Haskell. It sounded like a good name for a weapon-a well-sharpened blade, like scimitar or katana. The strong German-sounding plosive in its name, as in Nietzsche or Kafka, added a menacing edge. All I really knew about the language was that it was challenging and intended for math PhDs.

The rewrite could be done without knowing Haskell, technically, but I was an overeager graduate with a "challenge accepted" attitude to everything, even when it was absolutely uncalled for.

I found a whimsically titled tutorial book-Learn You a Haskell for Great Good!-and spent that winter writing Haskell most evenings after work. It was like learning to program all over again.

LONG BEFORE HASKELL coalesced into a programming language, it was a swarm of theoretical concepts. In 1977, the computer scientist John Backus delivered an influential lecture titled "Can Programming Be Liberated From the Von Neumann Style?" In it, he argued that existing languages were becoming bloated and ineffective. It was a clarion call to evolve "functional programming" from mathematical esoterica to a practical tool.

Programming paradigms are mainly divided into "imperative programming" and "functional programming." The dichotomy isn't clear-cut, as a growing number of languages support both styles, but for our purposes it may be enough to say that in imperative programming you write code as a series of steps, line by line, while in functional programming you define mathematical functions and let the machine worry about the steps. In terms of actual functionality and usage, imperative programming is the far more common approach.

Before Haskell, academic researchers had implemented certain functional concepts in the languages they worked with.

But in the late 1980s, a group of computer scientists came together to smelt them into a single language. They named it after the logician-mathematician Haskell Curry, whose work is foundational to programming language theory. (The original plan was to name it Curry, but the group soon realized a bullet dodged-that this would make it vulnerable to bad culinary puns.) The Haskell committee would blowtorch the messy excess of imperative programming with high-powered mathematics, sculpt a new chassis with the guidance of advanced logic, and weld everything together with modern compiling techniques. Out of the scalding forge, Haskell 1.0 was born.

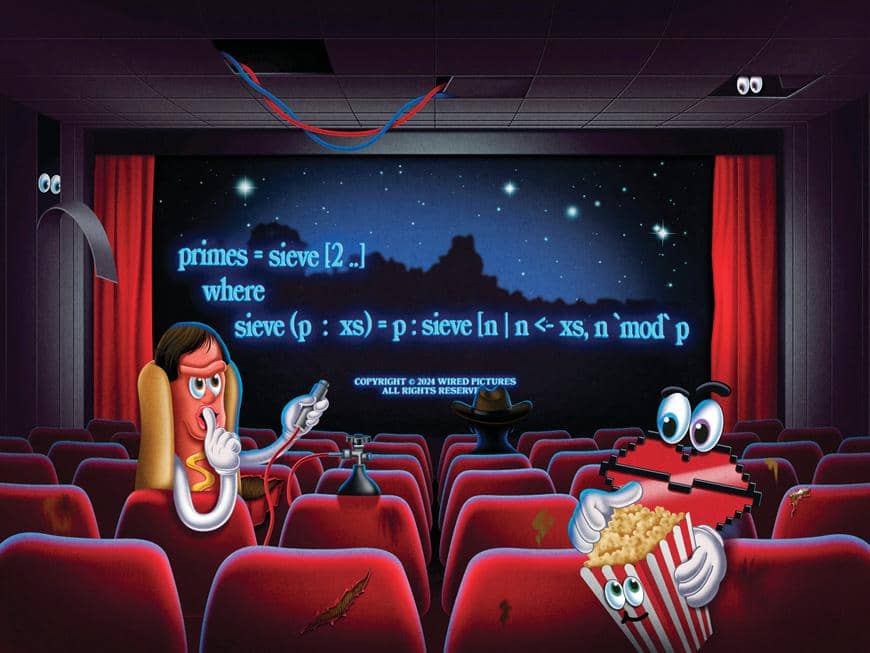

HASKELL SIMPLY LOOKED different from anything I'd ever seen. Spooky symbols (>>, <$>, <=, ) proliferated. The syntax was almost offensively terse. The code for the Fibonacci sequence, which can span multiple lines in other languages, can be written as a one-liner shorter than most sentences in this article: fibs = 0 : 1 : zip With [+] fibs (tail fibs). You might as well sign off each Haskell program with "QED." Whenever I set out to learn a new language, the first small program I try to write is a JSON parser, which converts a data format commonly used for web applications into a structure that can be manipulated by the computer. Whereas the parser I remembered writing in Chad resulted in a programmatic grotesquerie spanning a thousand-plus lines, I felt a frisson of pleasure when Haskell allowed me to achieve it in under a hundred.

At the same time, I understood almost immediately why Haskell was-and still is considered a language more admired than used. Even one of its most basic concepts, that of the "monad," has spawned a cottage industry of explainers, analogies, and videos. A notoriously unhelpful explanation, famous enough to be autocompleted by Google, goes: "A monad is just a monoid in the category of endofunctors."

The language is also more despised than explored. Steve Yegge, a popular curmudgeon blogger of yesteryear, once wrote a satirical post about how, at long last, the Haskell community had mana...