So the people have instead.

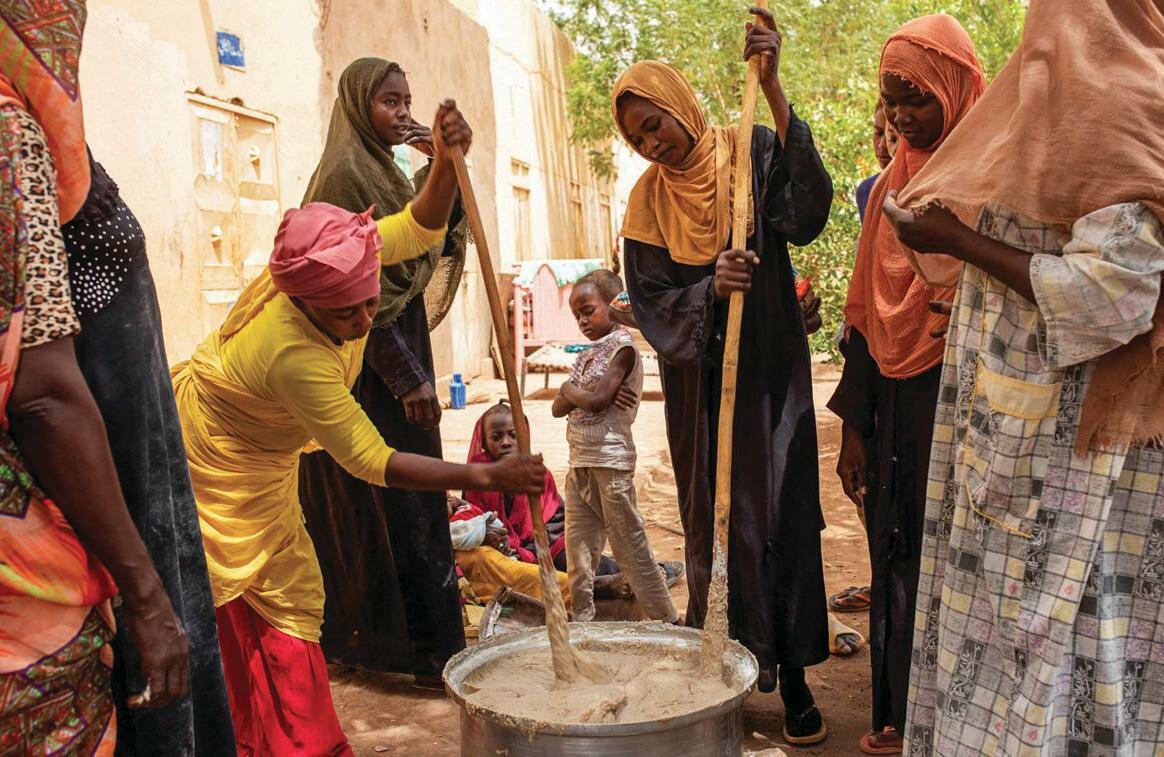

Across Sudan, ordinary citizens have organized themselves to feed their neighbors, accommodate strangers, rescue the wounded, and aid children traumatized by what is happening around them. More than 600 pop-up community centers, known as Emergency Response Rooms (ERRs), are now in operation, a grassroots effort that has become the central relief apparatus. Rising to meet a desperate need, the communal enterprise is also accelerating a global movement that represents a shifting tide in the way humanitarian aid is distributed, with reduced roles for major agencies and new prominence for locally led groups.

“We are helping our people,” says Hanin Ahmed, an early ERR organizer. “To save them. To bring food. To provide protection. We have women’s response rooms, trauma healing centers. We have children in alternative education, schools. We have a lot of stuff.”

The ERRs started when the fighting did. On April 15, 2023, a simmering rivalry between the head of Sudan’s armed forces and the leader of an allied militia erupted into full-blown war. With shells exploding across Khartoum, the capital, Ahmed and fellow students first mobilized to evacuate their university. The next day, a triage center was set up to sort which of the wounded should risk transport to hospitals. Next came a community kitchen, followed by counseling for victims of sexual assault.

Similar organizing was happening in other neighborhoods, in many cases led by people who had been active in the grassroots movement that four years earlier succeeded in toppling the military government that had ruled Sudan for decades. A transitional, technocratic government was put in place to guide the way to an election, but in 2021 it was forced out at gunpoint in a coup that produced the regime now fighting a staggeringly destructive war with itself. More than 11 million people have been forced from their homes.

THE WORSE SUDAN’S self-appointed leaders behave, however, the more nobly its people respond. In West Kordofan state, on the country’s southern border, Salah Almogadm had been working at the Ministry of Agriculture. His job disappeared with the war.

“There was complete paralysis,” he says. “There was no kind of government or health facilities.” Now, Almogadm, 35, helps manage local ERRs that feed 177,000 people a day. He agrees with what other volunteers have told him, that the work stirs one “to move forward, to serve.”

International aid groups try to help. But familiar agencies, the U.N. and private groups alike, find themselves sidelined by the fighting. Some are confined to refugee camps in adjoining countries like Chad. Many others are bottled up at Port Sudan, the Red Sea city from which the central government operates, since Khartoum remains a war zone. The best most can manage is supporting the ERRs.

“We have a convoy of assistance going into an area of Khartoum right now that hasn’t been reached since April 2023,” Taylor Garrett, the USAID response director for Sudan, told TIME on Dec. 20. “And the distribution network will be 70 ERRs plus 150 community kitchens.”

This plan is a change from the normal route of distributing via a handful of large international groups. Garrett expressed mild unease at the number of ERRs involved (“a lot more opportunities for something to go wrong”), but admiration at what they manage to do. “They are all prolific, and really force multipliers. The way this has taken off has allowed a lot more contact with affected communities than we ordinarily would have ... just more surface area.” That’s a good thing, he adds. “The scale of the people who need help is hard to grasp. I mean, it’s a huge crisis: 30 million-plus people in 2025 will need help.”

Not nearly enough aid is getting through. In late December, TIME spoke with four ERR volunteers on the ground in Sudan, patched through on WhatsApp by Ahmed, who is now based in the U.S. In North Darfur province, volunteer Mozdilfa Esamaldin Abakr spoke from a camp for displaced people.

“We have famine,” she said. “We are losing 20 children per day to starvation.” Most of the dead are between ages 2 and 3, she said. The local health center lacks lifesaving supplies such as rehydration solutions. “They have a section for malnutrition,” Abakr said. “But they don’t have enough, due to a lack of safe corridors, and also funds.” The town, El Fasher, is bombed daily by both sides—the regular army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the name given to the militia known as janjaweed when it was carrying out a genocide against non-Arab Sudanese in the same area 20 years ago.

“The security situation,” Abakr says, “is really bad.”

THIS IS WHERE international attention can make a difference. The ERR model recognizes that, even in the traditional structure of humanitarian aid, led by the U.N. and marquee agencies like CARE and Save the Children, local people did most of the crucial work, either as employees or volunteers. They are the ones who know the lay of the land, and where the needs are greatest. In locally led aid, much of the same essential work is done without the expense and trouble of outside managers, who have to be flown in, housed, and paid.

Sometimes called decolonized humanitarian aid, the locally led model is being endorsed even by some brand-name aid agencies, which have taken to boasting of their partnerships with grassroots NGOs. In Myanmar, where the government regards any aid entering conflict zones as support for insurgents, that can mean international groups operate almost clandestinely to get lifesaving provisions to the local groups that can distribute them.

But it’s also the locals who are always more vulnerable. For practical advice on staying safe, a grassroots aid worker might draw on the expertise of the Netherlands-based International NGO Safety Organisation (INSO), which works in 22 conflict countries, offering free training on security protocols and coordination. “Let’s say one NGO gets involved in an IED attack on a certain road in Jalalabad,” says Anthony Neal, policy director at INSO. “We want to ensure that other NGOs are aware of that incident.”

International outrage can play a crucial role by deterring violence in the first place. Attacks on large aid agencies can draw headlines that make even warring parties think twice, in part because their arms suppliers come under intense pressure. (In the Sudan conflict, the UAE is widely reported to be supporting the militia side, which it denies.) The goal, Neal says, is to “reaffirm the inviolability of the humanitarian worker” even if that worker is a volunteer rather than an employee of an international aid organization that can protect its own by lobbying governments and putting out the wo...