The food delivery company told Pedraza it needed help, fast. The pandemic's global lockdown measures would more than double demand for takeout orders to $51 billion that year. DoorDash was in a race with Uber Eats and Grubhub to find and sign new restaurants. Specifically, it needed assistance with the messy business of importing menus and pricing. The outsourcing shops that had typically done this work were now shuttered.

It was the deal Pedraza had been looking for. "I hate operations because it's friction all the way down, but that's why people buy it," he says.

Two years later, he got another call from a business struggling with an even bigger data problem. OpenAI wanted Invisible's help hammering the hallucinations out of what would become the model underlying ChatGPT. Contracts with Amazon, Microsoft and AI unicorn Cohere followed, helping skyrocket Invisible's revenue from $3 million in 2020 to $134 million last year, on which it made a profit of $15 million (Ebitda).

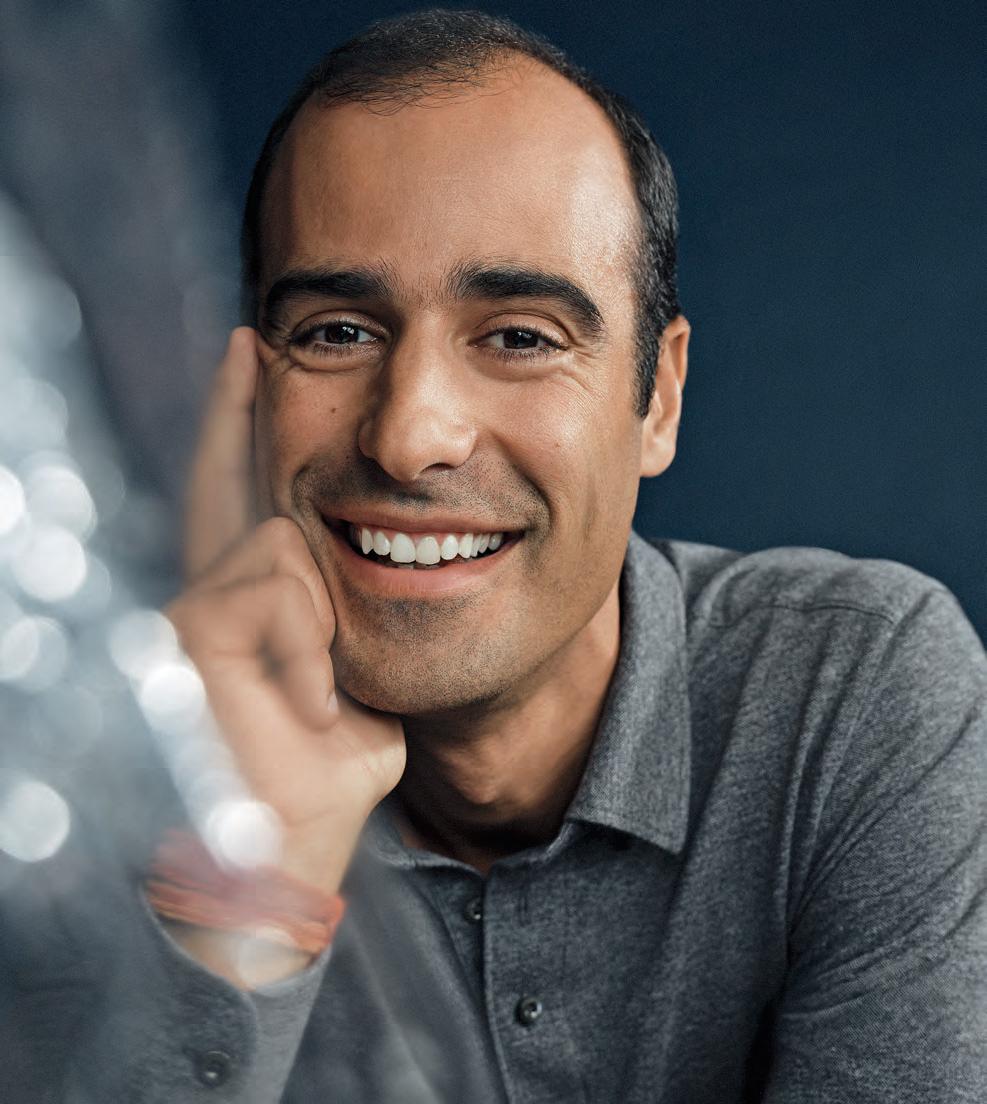

AI training has quickly become a crowded field with clickworker factories like Scale, Surge and Turing vying for the same jobs. But while Scale, living up to its name, raised $1 billion at a$14 billion valuation last year on $1 billion of annualized revenue, Pedraza, 35, is deliberately plotting a different path for Invisible, which claims to be remote (it's incorporated in Delaware; Pedraza is mostly based in New York City). The company raised only $23 million from investors—including VCs shops Day One, Greycroft and Backed-a drop in the bucket given the ongoing AI frenzy, and rather than selling off chunks of equity to more VCs, Invisible has been buying back its shares. "We could not be more different," says Pedraza, who retains an estimated 10% stake in his business, which was last valued at $500 million in 2023. (He generously granted the vast majority of shares to 300 or so of Invisible's current and former staffers, whom he calls "partners"—collectively, they own 55%, or around $1 billion apiece.).

Pedraza has borrowed $20 million over the last three years (first from a New York growth fund called Level Equity, more recently from JPMorgan) to buy out his early investors. "I believe that our equity would 10x in value, so it was an amazing arbitrage," he says.

It's a bold move, and unusual among VC-backed startups. Is paying interest (as high as 20% in the case of the Level Equity loan) the best use of Invisible's limited funds? And wouldn't that money be better spent on growth rather than effectively increasing Pedraza's stake? That decision was a no-brainer for Pedraza. Turning employees into (small) owners was his shortcut for high growth on a low budget.

A $500 million valuation (over three times revenue) seems modest for a service company, but shockingly low for an AI firm. When Pedraza bought out his "passive" investors in 2021, he wasn't just the only buyer—he also got to set the $50 million price. It was a good outcome for everybody, but the incentive was to keep the valuation low, he says.

Angel investor Edward Lando was one such seller after writing one of the first checks to Invisible at a $5 million valuation a decade ago. The company keeps doing really well, and I often wish I hadn't sold part of my position," he says.

Pedraza thinks it's a win-win. He gets more control. His early VCs-who long ago probably wrote their investments down to zero, get a clean exit.

An easy exit is especially appealing because Pedraza has been vocal about his intention never to sell Invisible or have an IPO. "You don't need to sell the company or go public, and that gives you more freedom," he says. VCs might also be eager to take the cash and lose the sophomoric posturing. Pedraza's rambling business updates are larded with references to Daoist philosopher Laozi, Napoleon and Ronald Coase, the Nobel laureate economist. "He's a visionary," says one clickworker who was recently let go. Former investors are more skeptical. "It's intellectual masturbation," says one.

Invisible is no...