Just when scientists thought they were beginning to piece together the puzzle, two new studies, published in January this year, threw a spanner in the works, challenging previous theories and adding new layers of intrigue to the FRB mystery.

"FRBs are one of these mysteries of the Universe that deserves to be solved," says Dr Tarraneh Eftekhari, a radio astronomer at Northwestern University, in the US, and lead author of first of the new papers published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. A solution may well be long overdue, but the Universe, it seems, isn't giving up its secrets just yet.

WHAT'S SO MYSTERIOUS ABOUT FRBS?

While it wouldn't be quite right to say that FRBs were discovered by accident, it's true that when first spotted, they were buried within data collected for an entirely different purpose: tracking down pulsars.

Pulsars, or 'pulsating radio sources', are a far better understood cosmic phenomenon. They were discovered in 1967 by Prof Jocelyn Bell Burnell and are known to originate from neutron stars – the incredibly dense remnants of massive stars that boast magnetic fields trillions of times stronger than Earth's. These fast-spinning stellar corpses emit regular pulses of radio waves, acting like cosmic lighthouses.

The regularity of the pulses Bell spotted, and the fact they were being emitted at a very specific frequency, hinted that they might be artificially, rather than naturally, generated and led her to nickname that first pulsar “Little Green Man 1”. But while pulsars quickly found their place in the astrophysical playbook, FRBs are a different story.

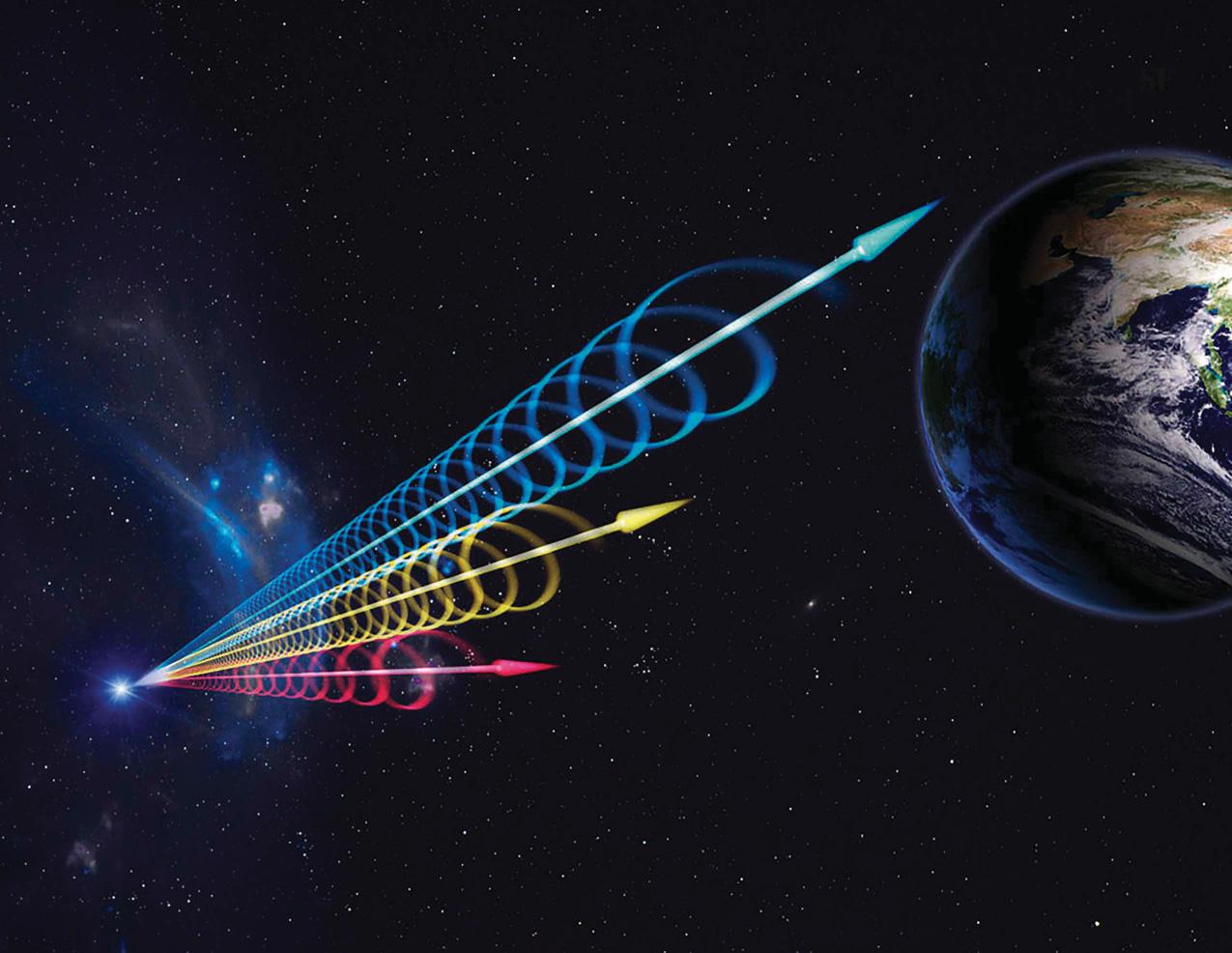

Fast-forward 40 years to 2007, when astronomers poring over data from the Parkes Multibeam Pulsar Survey (an international collaboration between groups at Jodrell Bank Observatory, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Bologna Astronomical Observatory and the Australia Telescope National Facility) stumbled upon something entirely unexpected: an ultra-short, incredibly bright burst of radio waves from deep space. This emission was so powerful that it outshone all other known sources at the time by a truly colossal amount.

In terms of energy output, an FRB that’s one millisecond long could emit the same amount of energy as the Sun produces in three days,” says Dr Fabian Jankowski, an astrophysicist specialising in FRBs at France’s National Centre for Scientific Research.

Yet, for more than five years after this first detection, no others were found, leading some to question whether FRBs were real at all. That scepticism faded as more began to surface. Since then, thousands have been detected, though astronomers estimate that two to three FRBs could be flashing across the sky every minute – suggesting we’re only aware of a fraction of the full amount.

Mysterious signals from deep space, emitting mind-boggling amounts of energy, filling the sky. So far, so strange. But the strangness doesn’t end there.

Initially, FRBs were thought to be one-off events - cosmic flukes, appearing once and never again. This assumption seemed solid; despite countless hours of follow-up observations, none of the sources ever repeated.

That changed in 2016, when an FRB known as FRB 121102 was spotted emitting repeated bursts. It's now thought that between 3 and 10 per cent of FRBs are so-called 'repeaters'. Why some FRBs emit a single burst and then remain stubbornly silent, while others emit multiple bursts is yet another mystery waiting to be solved.

WHAT'S CAUSING FRBS?

There are plenty of theories about what FRBS could be, from cataclysmic black hole collisions to aliens (even astronomers accidentally detecting meals cooking in their microwaves). But one candidate currently stands head and shoulders above the rest.

"We know that when very massive stars collapse and go supernova, they leave behind these highly magnetised neutron stars, or 'magnetars'," says Eftekhari. "The reason why magnetars are such compelling candidates for FRBS is that we've detected FRB-like events from a known magnetar that's in the Milky Way."

Neutron stars already boast incredibly strong magnetic fields, but magnetars exist in a league of their own, with fields thousands of times more powerful than an ordinary neutron star.

Adding to the weight of evidence stacked in magnetars' favour is that most FRBs are found in galaxies with high rates of star formation. This is key because, as Eftekhari says, “you need massive stars to go supernova and leave behind magnetars. And you find massive stars in galaxies that are producing stars.”

So,...